It’s difficult to talk about the history of jazz or blues music or dance styles without mentioning vaudeville at some point. Like many things it’s history is complicated and not all positive but it helps provide some context for these arts forms.

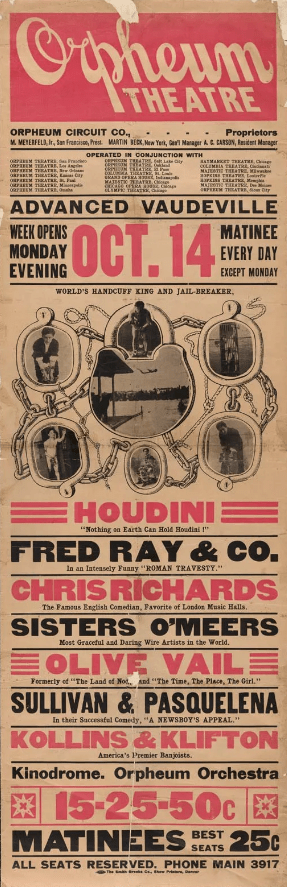

Vaudeville shows were a style of entertainment, of French origin, popular in the US from the mid-1800s to the 1930s. They were variety shows with a wide range of acts which might include dancers, sketch comedy, music acts, circus performers, burlesque, and later on short movies.

The history of vaudeville is inextricably intertwined with Minstrel shows which were a very popular form of variety show in many parts of the US throughout the 1800s. These shows featured black-face performances and grotesque racial stereotypes. They’re worth mentioning because the way that Black Americans were portrayed in minstrelsy had a profound influence on how Black performers and art forms were perceived and what audienced expected from Black performers for decades to follow. Minstrel shows depicted Black characters as naive farm workers or servants or as sensual exotic creatures and framed Black art styles as being wild and chaotic. By the 1920s Black art forms such as Blues music, Ragtime, and Jazz were becoming increasingly popular with white audiences but the creators of these art forms were still treated as second class citizens. Black vaudeville performers had a big job to do in breaking out of these negative stereotypes.

Many vaudeville shows would tour to a specific set of venues that catered to their target audiences. Different touring circuits catered to audiences of different classes or to specific groups – there were Italian and Yiddish vaudeville circuits. Mainstream vaudeville audiences were primarily white, however, a Black vaudeville circuit operated loosely from the 1880s and in 1920 the Theatre Owners Booking Association was formed. TOBA operated throughout the 1920’s and into the 1930’s (when it was replaced by the Chitlin Circuit).

TOBA booked Black performers exclusively and played to primarily Black audiences. Though TOBA artists were never paid as well as white vaudeville performers, they at least had the chance to develop a wider variety of more authentic performance styles. The TOBA circuit brought together a lot of great dancers and musicians of the time and offered them a chance to work together and to hone their skills. The Shim Sham tap routine was created by TOBA dancers and the Shim Sham break is still often referred to as the “TOBA break”

Vaudeville launched many careers for Black artists in the early 1900s. Vaudeville blues signers were the first Black music commercially recorded and most of these singers were women. A minority of Black vaudeville performers crossed over and performed on the white vaudeville circuits as well (sometimes in black-face) including the Whitman sisters and Bert Williams. Some vaudeville performers who went on to become international stars include Fletcher Henderson, Fats Waller, Ethel Waters, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Chick Webb, Cab Calloway, and Count Basie and also dancer including Josephine Baker, the Nicholas brothers, and Sammy Davis Jr (in vaudeville shows as a small child).

Vaudeville played a critical role in spreading music, dance, and entertainment trends, as well as cultural norms throughout the US before film and television came along and it’s legacy lives on even today in both positive and negative ways.

Further insights:

Blacks and Vaudeville (Youtube) a sometimes uncomfortable PBS documentary about vaudeville and minstrelsy

Black Entertainers on Vaudeville reflections on Vaudeville and TOBA from Thomas C Fleming

T.O.B.A. Time: Black Vaudeville and the Theater Owners’ Booking Association in Jazz-Age America, by Michelle R. Scott, a new book published just this year about the TOBA (we haven’t read this yet but definitely plan to pick up a copy soon!)