When you start looking into the history of Jazz or Charleston it seems like at some point all roads lead back to one place—Congo Square, New Orleans. ‘Congo Square’ or ‘Place Congo’ was a gathering place on the outskirts of New Orleans, Louisiana (now a part of Louis Armstrong Park). At some point around 1740 it became a place where enslaved Africans and free people of colour congregated. It may be that at one point many of the people congregating there had originally come from the African nation of Congo, though the word ‘Congo’ was also often used to describe any place or activity associated with people of African heritage.

In the 1700s New Orleans was still controlled by France (and also Spain for a bit) who were a bit more laid back than the other colonists on the continent. The Code Noir, enacted in 1724, allowed enslaved people in Louisiana to have Sundays off (though they still couldn’t legally gather anywhere). Eventually an old Native American ceremonial ground on the outskirts of the city was used as a place to congregate on Sundays and as a market to sell crops and prepared food.

These gatherings also involved music, dancing and religious practices brought over from West Africa. This made the Congo Square gatherings a unique phenomenon. In the other US colonies enslaved Africans would have had a harder time keeping their cultural traditions alive. African music was heavily suppressed due to fears that drums could be used as communication. It was also common practice for plantation owners to insist that enslaved people give up the religious practices of their homeland and adopt Christianity.

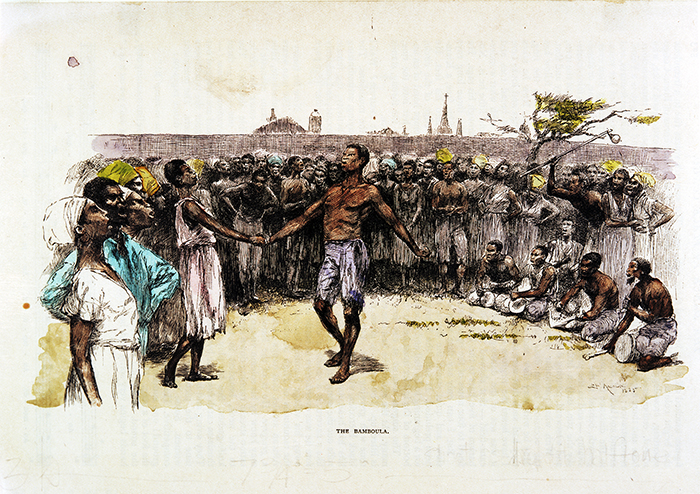

Around 1800 New Orleans experienced a large influx of both enslaved Africans and free people of colour after the Haitian revolution. This added event more diversity to the mix of people congregating in Congo Square. The music and dancing became a real spectacle with brightly coloured costumes and crowds of hundreds (maybe even thousands) gathering every week. White residents frequently stopped by to watch the spectacle from the side lines and it became a well-known tourist destination. These gatherings continued into the 1880s.

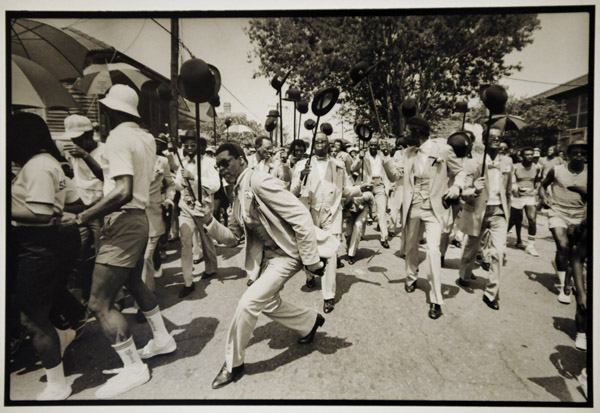

This excellent lecture from Freddi Williams Evans gives a good idea of what the music and the rhythm sounded like and draws a clear connection to the Second Line tradition that is still a big part of New Orleans culture today. A Second Line is a procession through the streets with a brass band and lots of people joining in and dancing done as part of a ‘jazz funeral’ and also for celebrations.

Second Lining became so popular by the turn of the century that a lot of brass bands were needed to cover all of the processions. All of New Orleans’ great early jazz musicians started out as second line players (King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Kid Ory, etc..). Buddy Bolden, the legendary first jazz musician, is known for having made a name for himself by adding African rhythms into marches (the popular music of the time). It’s thought that this provided an opening to bring more of the Congo Square rhythms into the second line. This signature New Orleans style music eventually developed into other styles of music like Charleston and Swing. Just like the music of Congo Square and the second line the music was made not just to be listened to but to be enjoyed viscerally with enthusiastic dancing!

Further Reading/Watching

Freddi Williams Evans: Congo Square. African Culture in New Orleans

Documentary on the New Orleans origins of Jazz

Congo Square: An Inquiry Into the Origins of Jazz